| Questing Exploration of Image, Symbol & the Making of National Stereotype |

Peter Lord |

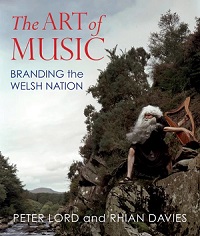

| The Art of Music: Branding the Welsh Nation- Peter Lord & Rhian Davies , Parthian Books , December 1, 2022 |

Parthian Books, most energetic and eclectic among the publishers of Wales, continues its strand of publishing books of weight on the visual culture of Wales. “The Art of Music” follows in the path of “the Tradition” (2016) and “Looking Out” (2020).

Parthian Books, most energetic and eclectic among the publishers of Wales, continues its strand of publishing books of weight on the visual culture of Wales. “The Art of Music” follows in the path of “the Tradition” (2016) and “Looking Out” (2020). The place of Peter Lord at the heart of Wales' cultural self-understanding goes back a quarter century. For this book two questing spirits join in an exploration of synergistic scholarship. Rhian Davies, a graduate of Aberystwyth, Oxford and Bangor Universities, is best known publicly for her programming of the Gregynog music festivals. Her career in music research, publication and documentary has been extensive. Covid-19 robbed the authors of visits to concert hall or gallery. This book was made over the months of lockdown. Art spans private and public life. This review appears on a site whose subject is performance for a reason. Performance runs throughout this tightly written survey of centuries of sound and image. The opening pages relate what may be a first account of a musical performance. In 1506 Sir Rhys ap Thomas held a grand tournament at his home, Carew Castle. “Sir Rice having reserved”, observes the contemporary observer, “a great companie of the better sort of guests, he leads them to the castle, with drummes, trumpets and other warlike musicke.” An early account of an appreciation of live music is here. Guto'r Glyn visits the Cistercians in Valle Crucis and writes: “Yno ar giniau organau- a dyf Cerdd dafod a thannau Ac yno mae'r Guto gau O fewn pyrth yn fanu parthau.” By 1568 abbeys and monasteries are pillaged ruins and performance has moved to the secular sphere. Plans for an Eisteddfod are underway for Caerwys with “mynstrelles, rithmers, or barthes”. Places of performance continue throughout the book: to Drury Lane, Wynnstay, the first venture into national theatre at Chirk Castle. Chapter 3, running to 56 pages, follows the rise of the Eisteddfod movement. Intricately detailed illustrations evoke the scenes at Cardiff in 1850, Rhuddlan in 1850 and Caernarfon in 1862 and 1867. The aims of the authors are stated concisely at the outset. There is a dissatisfaction that two art-forms have been treated in separation. The intent is to trace the grounding of Wales as “the land of song”, the process the “examining the role of pictures in the evolution of the trope”. The images of music and musicians that came to frame Wales were spread across canvases, lithographs, magazine illustrations and postcards. They entered the visual geography of the landcape; pubs with the name of the Welsh Harp or the Welsh Harper proliferated. Chapter 2 is called “the Construction of the Bardic Tradition” and runs to 64 pages. A full page shows the crucial image, the hugely influential “the Bard” by Philippe de Loutherbourg. The chapter has a further 33 images of harps and harpists of every size and medium. The rise of Wales as a place for travel of wonder is now recorded in the Sublime Wales research project of Michael Freeman and the Curious Travellers project at the Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies. Davies and Lord cite an instance of early travelling where music becomes a part of the experience of landscape. Mrs Thrale travels with Dr Johnson and describes a visit to Llanberis in her diary: “the wildest, stoniest, rockiest road I ever went...we found a Harper, and Mrs Wynn sang Welch songs to his accompaniment” By the 1820s the blend is well established, no tourism to wild Wales complete without the playing of a harp. “The fusion of bardic myth and observed if vestigial reality”, write the authors, “had firmly established the national brand in the mind of outsiders”. In 1848 the sculpture “The Death of Tewdrig” showed the wounded king with faithful daughter and faithful bard. At the Eisteddfod of 1848, Europe's year of revolutions, Carnhuanawc's opening remarks speak of a tranquil land: “might well royalty thus honour us, for while other nations are engaged in revolutions, the happy people of the principality are employed in composing odes for Eisteddfoddau and singing penillion with the harp.” But the cultural presentation of the happy people of the principality has an elasticity to it. There is a spice to the phrasing the authors use when they turn to the choral tradition. They write about the “fetishising of the male Welsh choir. It seems that - almost by stealth- male voices had usurped the place of the mixed choir, which had been central to the development of the choral tradition for most of the nineteenth century.” The interplay of the two art forms reaches a summation in painting with Ceri Richards. The pictures that evoke the sound of the drowned Breton cathedral of Ys prompt the critic Norbert Lynton to write “Here music, so often a guest in Richards' paintings, becomes a subject itself.” “The Art of Music” is rich in detail with an undercurrent to its journey across the centuries. The preface notes “the construction of symbols as archetypes and stereotypes”. It is joined to “the exploitation of the branding for wider political and societal ends.” The book records throughout the attention that power pays to culture. A half millennium ago government was suspicious. Some of the minstrels were considered to harbour “sinister usages and customs”. The Act of Union was intended to “extirpate” such customs and prosecutions of minstrels ensued. The same story, not in the book, is told elsewhere. Europe had a tradition of minstrels who travelled lightly with only zithers or guitars. They sang songs about free will and were known as the freedom people. Peter the Great did not like them at all. In 1700 he decreed there should be no more such people. Everyone should be part of an estate with fixed duties. By the time of 1618 in Wales the state is firmly in charge. At a masque “Pleasure Reconciled to Virtue” the Prince of Wales is hailed. “Calls tru hearts, that is us, he calls us, the Welse nation to be ever at your service, and love you and honour you.” In a vault over three centuries Brinley Richards is composing in 1873 “God bless the Prince of Wales”. Richards goes on to compose “Let the Hills Resound”. Following the winning of a prize the Prince of Wales invites a 500-strong choir to perform in the garden of Marlborough House. A future Empress of Russia is present. So too, as the authors phrase it, is “a gallery of London Welsh hangers-on, eager to be associated with national triumph.” There is a timeliness to the month of publication. The anthem of Dafydd Iwan lit the 2022 Eisteddfod and "Yma O Hyd" is being heard in a way that has no precedent. The authors take us back to the 1969 Investiture. The hugely popular song “Carlo” was disliked by the Caernarvon and Denbigh Herald who called it “a hymn of hate.” Iwan's song “Croeso Chwedeg Nain” followed in the same spirit: “Mae Mam wedi dysgu'r plant bach drwg sy' wedi mynd oddi ar y rels I ganu mewn falsetto “God bless the Prince of Wales”, Mae'r ffys wedi hala Wili'n od- mae'n siarad hefo fe'i hun, A Matilda yn y bathrwm yn dysgu “God save the queen.” Davies and Lord relate an episode of music's impact on politics. The sheet music of Ivor Novello's “Keep The Home Fires Burning” sold a million copies and was available in six languages. “In the USA", says the book, “it was influential in eroding isolationism and paving the way for American intervention in Europe.” In devolved Cardiff the tradition of Jennie Lee has long been lost. In this autumn of 2022 Sophie Howe, a loyalist at a state-financed event, spoke for the state capture of culture. Poets and playwrights are to be harnessed for government messaging. Happily, in a constitutional age culture lives within a dispersed ecology of power. Dawn Bowden may not command so has to stick to her feelings. “I feel the Arts Council of Wales can contribute to...Government” she writes 22nd December 2021. Indeed her feelings are so broad, on every subject except those artistic, that they run to 5000 words. The response of the Chair that charitable status forbids his taking political instruction is not made public. A former Chair was less inhibited on declaring his duty to the public. Geraint Talfan Davies: “the artists' role to question issues of state and to offer critiques of public policy- to challenge both rulers and the ruled.... throughout history, literature, plays and exhibitions have offered an alternative to issues on which there was a prevailing political orthodoxy.” “The Art of Music” takes on a complex subject of art and expression, symbol and stereotype, private performance and political framing. It is undertaken with finesse and economy, its narrative supported by 302 illustrations. Music scholar and historian of the visual arts have searched across continents to locate some of their images. “The Art of Music” has the unmistakable stamp of a leading company of Ceredigion to it. The print quality of Gomer runs across every page. A book of this type comes at a high cost. Acknowledgments are given to the Fitch Fund, the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, the Books Council of Wales, the National Library of Wales, the National Museum of Wales. the Rhys Davies Trust and the Estate of late John T Pickles. * * * * “The most difficult thing to predict is the past”: Peter Lord speaking at the National Museum about “the Tradition”, may be read in the sequence “On Criticism & Critics” 11th March 2016. Peter Lord's biography “Relationship with Pictures” is reviewed 4th July 2013 in the same sequence. The essay collection “Looking Out” is reviewed 14th December 2020. The sequence “On Criticism and Critics” can be accessed on the main reviews page at number 46 in the list of most read reviews. * * * * "Invented by an enthusiastic, and impassioned people, they partake of all the wildness of unrestrained originality: sprightly and Vivacious, plaintive and energetic." Accounts of music, hospitality and travel can be read extensively at: https://sublimewales.wordpress.com/material-culture/harpers/ |

Reviewed by: Adam Somerset |

This review has been read 936 times There are 4 other reviews of productions with this title in our database:

|