| Scale & Enquiry: An Exhibition Like No Other |

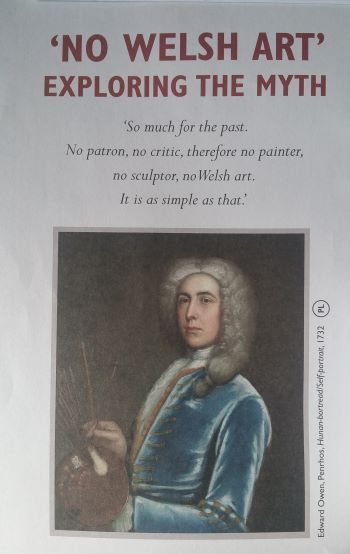

“No Welsh Art”: Exploring The Myth |

| Exhibition of 250 Artworks , National Library of Wales , September 11, 2025 |

“It would seem that the Welsh notice mainly their friends and that the surroundings melt into a kind of mist, as in the pictures of Beatrix Potter, which reflect the vision of a child.

“It would seem that the Welsh notice mainly their friends and that the surroundings melt into a kind of mist, as in the pictures of Beatrix Potter, which reflect the vision of a child. "Is the indifference to visual experience a matter of inheritance or simply of arrested development?” “The idea that the Welsh are unvisual has been and continues to be damaging to the health of the culture.” “The visual image is an essential medium for the assertion of national identity: the denial of the aesthetics of the one is the denial of the politics of the other.” These quotations appear in “The Aesthetics of Relevance” by Peter Lord. The first two paragraphs are from Donald Moore in 1987. The 55-page essay was published in 1992, part of a series from Gomer in 1992, edited by Meic Stephens. Peter Lord's argument extended to a section headed “the Idolatry of the Word.” Wales is a literary culture; the result is that regarding the tradition of visual culture “the greater the ignorance the greater the Welshness.” The thesis for this large and significant exhibition goes back a long time. The title was taken from words by Llewelyn Wyn Griffiths in 1950. Griffiths was the Chair of the Welsh Committee of the Arts Council of Great Britain. He subsequently became Deputy Chair of the Council itself. The exhibition comprised 250 images; painting predominated but drawings, prints, mezzotints and sculpture maquettes also featured. The display blended the collection of Peter Lord with artworks held by the National Library. The larger proportion belonged to the private collection of Peter Lord. It ran from 16th November 2024 to 6th September 2025. Exhibitions have two elements. One is the content; the second is the critical engagement that it engenders. That second element will be the subject of a second article. The language of curation has a convergent tendency in these days. That used in the exhibition went against the grain, being direct and related to the artworks on show. It had a pungency of character to it. Thus the stance of Wyn Griffiths: “He had internalised colonialist attitudes that despised the cultural product of Wales where it did not reflect that of England.” The last part of the exhibition moved to the fiery days of the 1980s. "Ty Haf”, an explosion of dense pigment by Peter Davies, was shown as part of a group exhibition in Bangor in 1984. The day after the exhibition opened, ran the accompanying text, “the painting was removed from the wall, censored by the gallery curator.” The context of the Beca group was given as: “London governments perceived as hostile to Welsh cultural and economic interests and to national aspirations stimulated a political reaction that was manifested in visual imagery from the 1970s. Through a joint identity the artists' group Beca pursued a political agenda, establishing contacts and exhibiting with sympathetic groups and individual groups outside Wales, but bypassing London. At home activism involved the production of visual propaganda, attacking not only English colonialism but the escapist tropes of a compliant domestic culture.” The chronology started with eighteenth century patronage, which moved from aristocracy to middle class, the employment of established names in England to local artists. The artisan painters produced portraits running into the thousands. One of the most accomplished was Hugh Hughes, his study of a mother with her two daughters an exhibition highlight. With the formation of a concept of Britain- historian Linda Colley is its best describer- subject matter turned to allegorical representation of the nations. The National Revival saw a focus on figures from both history and legend. “The Last Bard”, who features strongly in Peter Lord's last book with Rhian Davies “the Art of Music”- became a symbol for a benign poetic and musical temperament. The Romantic re-imaging of the Welsh landscape saw the arrival of artists from England; Betws-y-Coed is identifiable as the first artists' colony in Britain. Women artists late in the Victorian age joined to form the Gwynedd Ladies Art Society. Lady Augusta Mostyn built Britain's first gallery intended to show women artists. Art goes hand in hand with its interpretation. The exhibition narrative caught a paradox in the critical record: “Before the Great War, much writing focussed on the idea of national styles, expressive of “indigenous” characteristics, represented in Wales by the idea of the emotional and poetic Celtic temperament. This presented a difficulty, since the painter Richard Wilson and the sculptor, John Gibson, frequently held up as exemplars for the nation's greatest accomplishments in the field wre both Classicists.” Industrial Wales of the twentieth century had its artist-witnesses in figures long championed by Peter Lord: Evan Walter, Archie Rhys Griffiths, Vincent Evans. In “Their Burden” Maurice Sochachewsky made a striking image with a palette of tonal subtlety. The primary visual trope of Wales moved from the heights of Eryri to the valleys of the south. Glyn Morgan's “Tonypandy” from 1951 had words of the painter to Winifred Coombe Tennant to accompany. “How can one mortal painter hope to put down all that mystery and dignity? They can keep Switzerland. I should like to have a large studio on wheels, thousands of canvases, and two lifetimes to paint the Rhondda valley.” The narrative of the exhibition picked on a particular cultural feature in a section entitled “the Pious People.” A striking study of a chapel interior with figures by John Elwyn from 1950 is titled “the Faithful Few.” “The idea of the moral superiority of the common people of Wales over their English contemporaries”, read the text, “was central to many Welsh intellectuals in the period.” The anti-chamber to the.Gregynog Galleries themselves included artistic self-imaging by Shani Rhys James and John Cyrlas Williams. A 1980's picture powerfully gave a new allegorical version of the nation as a pierrot along with a sagging Union Jack. The force of the image coincided with a change in the artists themselves. Since the 1970s a greater number has opted to remain within Wales. The accompanying text to a magisterial exhibition closed with a change from statement to question: “Do Welsh artists have a particular responsibility to challenge the nation's historic inheritance of a colonialised mentality?” “In an increasingly globalised economic, cultural and political context, how can Welsh artists speak with confidence and relevance both to the nation and to the world?” |

Reviewed by: Adam Somerset |

This review has been read 108 times |